How to Open a Bank Account That No Creditor Can Touch

Published on: 12/04/2024

You have options that can help you safeguard your money from creditors seeking to freeze or garnish your bank account, but some may be more reliable than others. Bank accounts solely for government benefits and accounts opened in states that limit garnishment are important options to remember.

If a creditor or debt collector has sued you and a court has ruled against you, the plaintiff may be able to garnish your wages or bank account — both a savings or checking account. If you want to create a strategy to shield your funds from garnishment, this article shows you how to open a bank account that no creditor can touch and offers some tips on understanding wage garnishment.

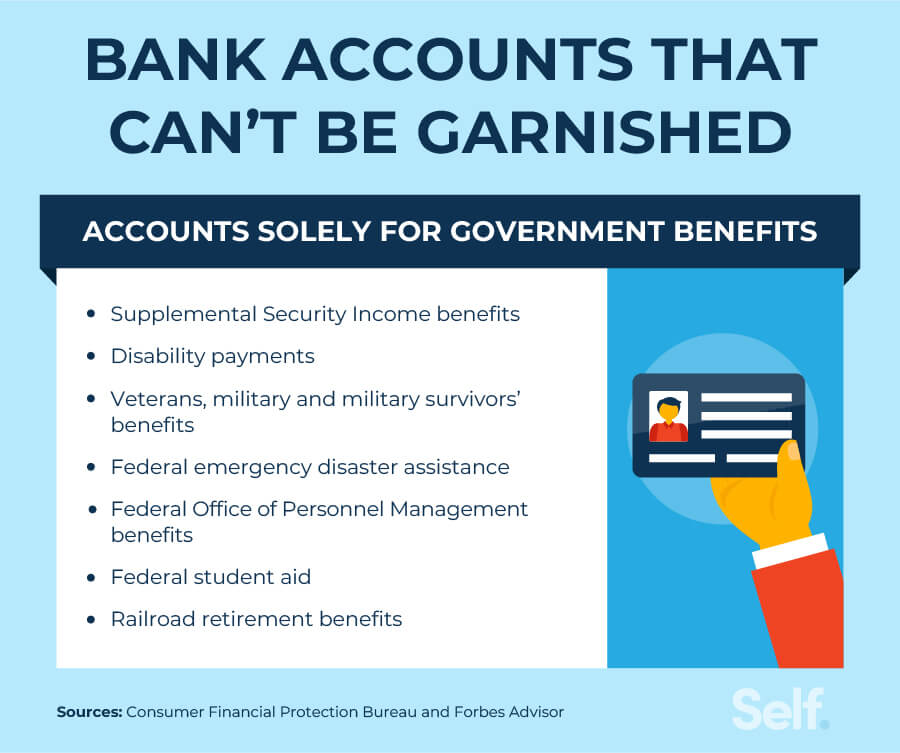

Bank accounts that can’t be garnished

Also known as an exempt bank account, a bank account that can’t be garnished helps protect your personal finances if you fear a court might order you to pay a creditor. A garnishment order may not apply to some kinds of accounts, depending on factors that may include the source of the money deposited there, how it’s deposited and where the account is located.

Bank accounts solely for government benefits

Federal law ensures that creditors cannot touch certain federal benefits, such as Social Security funds and veterans’ benefits. If you’re receiving these benefits, they would be exempt from garnishment. If you qualify but haven’t applied for these benefits and you think you may be subject to garnishment, be sure to have these benefits directly deposited into your account to protect against garnishments.[1] [2]

For these funds to be protected from garnishment, they must be made by direct deposit into a bank account — not by check — so they can be traced to the exempt sources. Otherwise, they will no longer be protected against garnishment. Only two months of these benefits, with some caveats, can be protected, so any amount you’ve accumulated above two months’ worth of benefits is not protected. However, if that extra money that is garnished is exempt from garnishment under federal or state law, you may be able to go to court to have your money released. To ensure you understand your rights under wage garnishment and what benefits may be subject to garnishment, you should seek the advice of an attorney.[2]

In addition to the government benefits discussed above, the following can’t be garnished:

- Supplemental Security Income benefits

- Disability benefits

- Veterans, military and military survivors’ benefits

- Federal emergency disaster assistance

- Federal Office of Personnel Management benefits

- Federal student aid

- Railroad retirement benefits

[3]

Bank accounts outside of your home country

Bank accounts in other countries may be exempt from garnishment as well. Offshore bank accounts are often mentioned as money shelters. While offshore accounts aren’t illegal, hiding money in them is. Using offshore accounts to avoid state or federal taxes is unlawful, and even money that isn’t subject to taxes has to be declared if it’s held offshore.[5]

Offshore trusts may offer asset protection, but you risk the following disadvantages:

- Cost: You may incur a lot of expense to open an account.

- Access: You may have a harder time getting your funds.

- Loss: You risk losing your money if the bank fails because your assets won’t be protected by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

[6]

Can a joint account be garnished?

Whether or not a joint account can be garnished depends on the laws of the state where you live.

Joint accounts in community property states

If you live in a community property state and a creditor gets a judgment against your spouse, they can garnish from your joint account. In some instances, even if you have your own separate bank account, a creditor can still garnish it to repay your spouse’s debt if a judgment is taken against them. However, there are some exceptions depending on your state. You may wish to check with an attorney or do your research to understand your rights in the state you live in.

Common law or separate property states

Different states handle marital debt differently. In some common-law or separate property states, creditors cannot garnish a joint account unless a debt was taken jointly or benefitted both parties. So spouses with separate finances typically may not be responsible for each other’s debt.

However, when it comes to joint accounts in these states, a creditor may be able to garnish up to half the funds in the account even if you weren’t liable for the debt. On the other hand, other separate property states may not allow garnishment of the account if you’re not liable for the debt, unless you both benefited from the debt or it was incurred to gain joint property.[4]

In either case, private debt collectors typically must obtain a court order to access your bank account in an attempt to secure money owed on credit cards, auto loans, mortgages, personal loans, and other debts.[3]

What other options do I have to avoid wage garnishment?

Rather than trying to avoid a creditor, consider meeting your debt head-on by taking one of the following steps:

- Negotiate a debt settlement plan with the creditor. If you can’t pay the entire amount at one time but think you might be able to pay some over time, contact your creditors to see if you can work out a settlement plan. Although your creditors may agree to a reduced amount, you still may be able to negotiate the terms, such as establishing an installment payment schedule.[7]

- File for an exemption from garnishment. Even though some federal benefits are protected from garnishment, if you believe garnishment would create a hardship for you, you can check to see if you qualify for any exemptions. Exemption types, qualifications and how you file for them differ by state. So find an attorney who specializes in collections for legal advice about your situation and options.[8]

- Discuss bankruptcy options with an attorney. As a last resort, you may want to look at bankruptcy options. Discuss your situation with an attorney who specializes in bankruptcy cases to see if this is an option for you. Although bankruptcy can shield you from some kinds of debt, remember that exceptions exist. You may not be shielded from child support or spousal support, as well as federal or state tax debt and many student loans, plus you may need the bankruptcy option later.[9]

How are wages garnished?

Debt collectors and creditors can only garnish your wages once they obtain a court order called a garnishment order or writ of garnishment. The court order permits employers to withhold some of your earnings to cover the debt you owe. Federal benefits are typically exempt from garnishment unless they’re being used to pay child support, student loans, delinquent taxes or alimony.[10]

These four states fully protect wages from garnishment:

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- South Carolina

- Texas

Be aware: Creditors can try to get around state-imposed limits. For example, you may have a bank account in one of the four protected states, but if your employer has an office in another state, a creditor may try to circumvent that protection by seeking to garnish your wages in that state instead.[11] Also, some banks in states that offer protections may require that you reside in that particular state.

While creditors may not be able to garnish your wages in these states, they can still attempt to garnish your bank account.

In addition to garnishing your wages, a creditor can also obtain a judgment to levy your bank account. This causes the bank to freeze your account and send the creditor what you owe them. You won’t be able to access your account until the debt is paid.[12]

What can be garnished?

Debt collectors can garnish your wages with a court order, but the government can also use garnishment to recover what you owe. Various kinds of debt that may be subject to garnishment include:[3]

- Consumer debts

- Delinquent taxes

- Unpaid alimony

- Unpaid child support

- Unpaid student loans

How quickly can creditors garnish wages?

How long this process takes relies primarily on the state in which the case is filed and the court’s specific order. To best understand how the process works in your state and the timeline you’re facing before your wages are garnished, see the legal counsel of an attorney who specializes in collection and garnishment cases.[13]

Can my bank account be garnished without notice?

Creditors and debt collectors have to inform you of the lawsuit against you that leads to your bank account being garnished, they do not necessarily have to warn you before the garnishment happens. Some people may be unaware that their bank account will be garnished until after it happens. This is why it’s important not to ignore legal letters from creditors or debt collectors.[16]

Can a savings account be garnished?

Yes, creditors can garnish your savings account as well as your checking account, providing that the money you have saved has not come from sources like Social Security, child support, or other types of government benefits. Retirement funds from pensions and annuities are also exempt from garnishment by creditors.[17]

Maximum amount of wage garnishment allowed

Not all of your wages will be garnished at once to pay off your debt — just a percentage.

Title III of the Consumer Credit Protection Act (CCPA) limits how much of a person’s earnings are subject to a creditor garnish. This law ensures that individuals whose money is garnished have enough left to meet living expenses. Under the CCPA, an ordinary wage garnishment can’t exceed one of two figures: 25% of an employee’s disposable earnings or earnings that are greater than 30 times the federal minimum wage.[14]

With the federal minimum wage being $7.25, you wouldn’t be garnished for anything up to $217.50, or $7.25 times 30. Up to $290, above $217.50 the amount above may be garnished, and for disposable earnings higher than $290, a maximum of 25% of disposable earnings may be garnished.[14]

Why would a bank levy be used over wage garnishment?

A bank account levy is more severe than wage garnishment because the court allows a creditor to freeze the money in your account.[12] Wage garnishment, by contrast, is limited to a percentage of your disposable income. As a result, a creditor may prefer to use a bank levy to recoup as much of a debt as quickly as possible.

Pay back your debt

You can avoid creditor garnishes and bank levies by getting your finances in order. Adopting strategies to pay off credit card debt and other obligations faster can preserve your personal funds.

- Pay above the minimum each month. Paying a larger amount of money than the minimum keeps interest from accumulating and allows you to pay off your loan more quickly.

- Pay multiple times a month. Making more than one payment a month can reduce your debt faster.

- Use the snowball method to pay off debt. This method of tackling debt involves paying off your smallest debt first, then rolling what you had paid on that bill into the next-smallest balance, and so on. This way, you gain momentum toward paying off all your debt.

- Monitor your bills and spending. Making a budget and staying on top of your payments through strategies such as automatic bill pay can keep you from incurring extra fees and added interest.

[15]

If you find yourself owing more than what you can afford, think about negotiating with your creditors to agree on a repayment plan or debt settlement before your creditors seek a court order. Failing to pay your debts can impact your credit report and damage your credit score as well. Following the tips in this article to pay back debts rather than avoiding them, may benefit you in the long run.

Disclaimer: Everyone’s situation is different. If you have concerns about wage garnishment, consult a lawyer.

Sources

- USA.gov. “Government Benefits,” https://www.usa.gov/benefits.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “Can a debt collector garnish my bank account or my wages?” https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/can-a-debt-collector-take-my-social-security-or-va-benefits-en-1157/.

- Forbes. “Can A Debt Collector Get Into My Bank Account?” https://www.forbes.com/advisor/debt-relief/can-debt-collector-get-into-bank-account/.

- NOLO. “Bank Levies on Joint Accounts (Spouse),” https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/bank-levies-joint-accounts-spouse.html.

- Investopedia. “Offshore Banking Isn’t Illegal, But Hiding It Is,” https://www.investopedia.com/articles/managing-wealth/042916/offshore-banking-isnt-illegal-hiding-it.asp.

- Money Alert. “Offshore Banking Pros and Cons,” http://www.themoneyalert.com/offshore-banking-pros-and-cons/.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “What is the best way to negotiate a settlement with a debt collector?” https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-the-best-way-to-negotiate-a-settlement-with-a-debt-collector-en-1447/.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “How do I find a lawyer or attorney to represent me in a lawsuit by a creditor or debt collector?” https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/how-do-i-find-a-lawyer-or-attorney-to-represent-me-in-a-lawsuit-by-a-creditor-or-debt-collector-en-1433/.

- Experian. "What Is the Difference Between Chapter 7 and Chapter 13 Bankruptcy?" https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/bankruptcy-chapter-7-vs-chapter-13.

- Federal Trade Commission. “Debt Collection FAQs,” https://consumer.ftc.gov/articles/debt-collection-faqs.

- NCLC. “Protecting Wages, Benefits, and Bank Accounts from Judgment Creditors,” https://library.nclc.org/protecting-wages-benefits-and-bank-accounts-judgment-creditors.

- Forbes. “How To Fight A Creditor’s Levy On Your Bank Account,” https://www.forbes.com/advisor/debt-relief/how-to-fight-creditors-bank-account-levy/.

- Chron. “How Long Does it Take to Garnish Wages?” https://work.chron.com/long-garnish-wages-17434.html.

- U.S. Department of Labor. “Fact Sheet #30: The Federal Wage Garnishment Law, Consumer Credit Protection Act's Title III (CCPA),” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/30-cppa.

- Wells Fargo. “How to Pay Off Debt Faster,” https://www.wellsfargo.com/goals-credit/smarter-credit/manage-your-debt/pay-off-debt-faster/.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “Can a Debt Collector Take or Garnish My Wages or Benefits?” https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/can-a-debt-collector-take-or-garnish-my-wages-or-benefits-en-1439/.

- United Way. “Avoiding Account Garnishment” https://www.unitedway.org/our-impact/financial-security/my-smart-money/avoiding-account-garnishment.

About the author

Ana Gonzalez-Ribeiro, MBA, AFC® is an Accredited Financial Counselor® and a Bilingual Personal Finance Writer and Educator dedicated to helping populations that need financial literacy and counseling. Her informative articles have been published in various news outlets and websites including Huffington Post, Fidelity, Fox Business News, MSN and Yahoo Finance. She also founded the personal financial and motivational site www.AcetheJourney.com and translated into Spanish the book, Financial Advice for Blue Collar America by Kathryn B. Hauer, CFP. Ana teaches Spanish or English personal finance courses on behalf of the W!SE (Working In Support of Education) program has taught workshops for nonprofits in NYC.

Editorial policy

Our goal at Self is to provide readers with current and unbiased information on credit, financial health, and related topics. This content is based on research and other related articles from trusted sources. All content at Self is written by experienced contributors in the finance industry and reviewed by an accredited person(s).